When OpenAI announced the release of deep research last year, they rightly said “the ability to synthesise knowledge is a prerequisite for creating new knowledge”. The same can be said for individuals and companies.

However, while many have been able to make use of deep research in an individual context - searching and synthesising information online - few have benefited from it in an enterprise context. That isn’t because it wouldn’t be useful (quite the opposite), but because of wider concerns around reliability, disparate data sources and/or a model’s ability to deal with large amounts of context (think vast numbers of varying file types).

Our experience building enterprise-grade deep research tools in the last 12 months have shown that those concerns can increasingly be mitigated by thoughtful engineering. In this blog, we discuss the major blockers to effective enterprise deep research applications, how we'd overcome them and how we see the space developing over 2026.

Executive Summary: The State of Enterprise Deep Research in 2026

- The execution ceiling has jumped dramatically. The arrival of gpt-5 in August 2025 marked an inflection point for enterprise AI. In our production systems, including a drug target discovery platform for one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, we saw source hallucination drop from 3-4% to effectively zero. gpt-5.2 in December then pushed effective context length further. The practical result: we can now scale from hundreds of sources to thousands per research run, without sacrificing reliability. The bottleneck has shifted from model capability back to where it belongs—your data, your evals, and your program design.

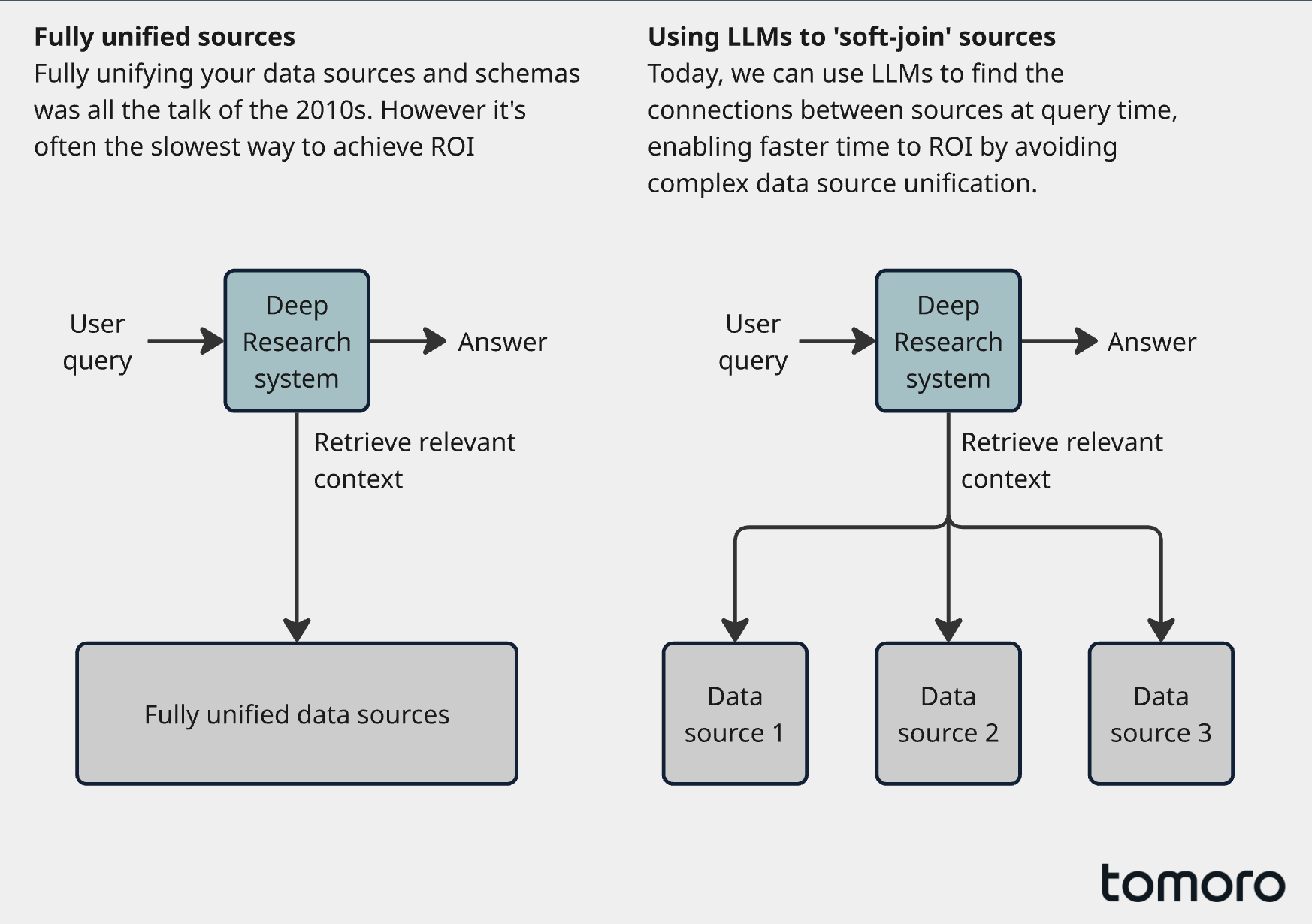

- Data strategy: reachable beats unified. The instinct to treat enterprise AI as a data integration problem is understandable but often counterproductive. Full unification is slow, political, and forces premature commitment before you’ve learnt which questions actually matter. The pragmatic move in 2026 is sparse connectivity. Make data reachable via high signal anchors (specs, policies, SKUs, contract clauses) rather than waiting years to unify everything. Frontier models can now ‘soft-join’ across systems at inference time, bridging connected terms without formal mappings. You keep your speed to deployment and your flexibility to add sources later.

- Navigation prevents wandering. Enterprise data isn't the web. It's sparse, full of local conventions, and often has exactly one right source for a given fact. Without guidance, models have a tendency to churn through endless queries to find just one more source, burning through latency and user patience in the process. A lightweight semantic layer (hash maps, entity lookups, thin relationship graphs) gives the system fast, low-cost moves to reach the right context efficiently. Think of it like the advice a seasoned colleague gives a new hire: "bookmark these sites, talk to Ross if you have AWS issues." It doesn't need to be complicated. It just needs to help the system find what it needs quickly.

- Structured evals replace vibes. Many enterprise AI projects die in the gap between “impressive demo” and “reliable at scale”. The culprit is often vibes-based evals: run a query, read the output, nod approvingly, ship it. That approach collapses when your system is autonomously traversing 5,000 documents to inform a multi-million dollar decision. Reliability requires a three-tier evaluation stack:

- Mechanical (run on every query): Citation health, tool hygiene, latency and cost. These are your guardrails, mundane but essential.

- Analytical (run periodically): Is the system choosing the right tools, pursuing sensible research directions, selecting authoritative sources, knowing when to stop? Typically scored via LLM-as-judge against labeled examples.

- User (ongoing): Task completion rates, qualitative feedback from power users, usage analytics. The ultimate test. Have we built something that people find useful?

- ROI comes from hard problems, not safe ones. In the wake of reports claiming most enterprise AI projects fail to achieve ROI, the tolerance for impressive demos that don't ship has evaporated. Executives want proof, and they want it fast. That pressure, paradoxically, can push teams toward the wrong choices. The temptation is to start with low-stakes tasks because they're easy to deploy and unlikely to ruffle feathers. But these use cases rarely move the needle enough to justify continued investment. Enterprise deep research systems are well positioned to prove value because they target work that's already expensive: complex, high-stakes workflows where the cost of the status quo is visible. The strongest use cases we've seen are in areas like RFP and bid generation, scientific landscape analysis, and investment research—domains where impact is measured in win-rates, faster paths to trial, and speed to conviction, not just hours saved.

- The UX shift: from chatting to delegating, from answers to artefacts. We think this is one of the user experience shifts that will define 2026. When we look at the builds that have seen the strongest adoption recently, a couple of things stand out. As the reliability of these systems has increased, users have started treating them less like a chatbot to query and more like an analyst to delegate to. Two things make this possible: giving teams the ability to customise templates and stopping criteria to fit their specific workflows, and letting them export directly into the format they actually need (a memo, a deck, a brief, etc.) rather than asking them to compile a finished deliverable from a chat thread. When both of those are in place, the system stops being a reference tool and starts being how work gets done.

Deep Research over Enterprise Data Remains a Core Focus

Last year we wrote about bringing deep research to the enterprise. With this we took the web-centric deep research paradigm initially popularised by OpenAI, and extended it to companies’ proprietary data sources without losing provenance or control. We also made the point that deep research systems should not be thought of as a departure from more classical RAG systems, rather as an evolution of them.

What’s changed going into 2026 is less the idea of deep research and more the ceiling at which it is possible to execute.

When we started building these systems early in 2025, frontier models included o1, gpt-4o, and claude-3.5-sonnet (we really have come a long way in 12 short months…), with big steps coming with the models like o3 and gemini-2.5-pro in the first few months of the year. These were great for their moment and one absolutely could build robust deep research applications with these, up to a point. That point was typically around the low hundreds of sources, after which you would have to prune your context quite aggressively or else pay the price of a lossy answer, breakdown in instruction-following, or outright hallucinations.

If you’ve built these systems you’ll recognise some of these failure modes.

To bring this to life a bit: In mid-2025 Tomoro began building out an enterprise deep research solution with one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies—this is a system to accelerate drug target discovery, a process wherein researchers search for genes, hormones, or other things in the human body that can be targeted to treat a condition. At the time, the strongest model available was o3. While this delivered a strong level of performance, 3-4% of responses generated by this model would contain sources that had not been provided to the model via tool calls from the client’s proprietary data sources. We mitigated this with post-hoc citation checks, which flagged sections of answers which were unsupported by the provided context. This worked well for building stakeholder confidence in the tool in what was an early PoC stage of the project and helped us make progress quickly. But, we continued our efforts to drive down these errors, trying to mitigate the limitations of the models while delivering on stakeholder asks for further sources to be added to the system.

A key inflection point for building frontier deep research solutions (and agentic solutions more generally) came with the advent of gpt-5 in August. Upon swapping from o3 to gpt-5 our evaluations showed that source hallucination rate dropped immediately to 0%.

To be precise about this metric: this tracks strictly whether the model cites a document ID or URL that was not present in the retrieved context. In the era of o3 (and before), models would sometimes invent plausible-sounding filenames or papers to fill gaps in their knowledge. gpt-5 allowed us to effectively eliminate this specific pathology.

Note that this is distinct from faithfulness errors (citing the right document but misinterpreting the text), which remains a challenge we manage via the post-hoc checks mentioned above.

This was a huge unlock. With this, we began testing the system to see just how far we could push it with the new generation of models. We found that we were able to roughly 10x the number of sources we could consider on a deep research run (to around 3-5,000), and the limit we ultimately hit was not a breakdown in instruction following and instead long-context performance (the effective context length of models is often far lower than the reported one, especially with e.g., dense pharmaceutical data).

This restriction was partially alleviated with the release of gpt-5.2 in mid December. Our internal long-context benchmarks indicated that this delivered a strong step up in the effective long-context performance, enabling us to push our frontier deep research systems even further. This was useful as it allowed us to ultimately increase the number of tokens that can be passed directly to the model which produces the output for the user, thereby delivering a richer answer. Though we would like to continue to see the effective context lengths of frontier models continue to increase into 2026.

Given these advancements in raw model capability, the bottlenecks for building capable deep research systems have in many ways shifted back to where it should have been all along: your data, your evals, and how you set up your deep research program in your business. Each of these steps requires you to make pragmatic decisions about what helps move the needle in a deep research build.

The rest of this article outlines how we think about those decisions.

Getting Your Data Right

A tempting move can be to treat enterprise research projects as a data integration problem. Unify the sources, normalise the schema, and let the models loose on top.

And to be clear: sometimes that’s exactly the right move. If you’re operating in a domain where the core entities are stable, the queries are repeatable, and you’re ultimately trying to industrialise the workflow then unification can pay real dividends. Classic cases include joins of customer and revenue data, market pricing data, or anything where you need reliable, cross-system reporting.

However, in practice, the innovative leaders of today are looking for something different from enterprise deep research systems.

With an ever-increasing focus on the ROI from AI spending, a key objective for decision makers is to prove value quickly in the messy reality of how the business actually works. And full data source unification is one of the slowest ways to get to that first proof. It’s heavy. It gets political. And often it forces you to commit to a direction before you’ve learned which questions actually matter.

So, we believe the pragmatic starting point for building frontier deep research systems in 2026 is usually this: make your data reachable, before you make it beautiful.

If you have a realistic prospect of adding more sources over time (most enterprises do) then sparser connectivities are underrated. You can expose tens of sources behind a consistent retrieval contact. The system will still be able to work, and critically you keep your ability to deliver quickly. When you come to adding more sources, you don’t have to move the world. You simply can attach a new connector, explain to the core system what it is and how to use it, and let the models take it from there. This works because frontier models today can soft-join two or more data sources at inference time, bridging “Customer ID” in one system to “Client Reference” in another, without anyone writing a formal mapping. We’re not the only team thinking this way. We're not the only team thinking this way: OpenAI's internal data agent is designed to let models reason over 70,000 heterogeneous datasets by making context and connections reachable at query time, rather than forcing full upfront unification.

One nuance it’s worth making explicit here is that sparse does not have to mean shallow.

Sparse integration works best when the connections you do make are meaningful and are expressed in a way that the system can easily exploit. A good way to think about it is to treat certain pieces of information as anchors (specifications, policies, product definitions, SKUs, contract clauses and the like). You don’t have to unify every dataset to make these anchors powerful, you just need a stable identifier with a few high-signal edges.

For example, imagine a model (or a user) looks up a specification. In a naive system, that’s where the interaction ends. You fetch the spec, you summarise, maybe you cite it. However, when we think about building useful data structures we want to translate that lookup into the start of a controlled expansion. For example, we could optionally link that specification’s record out to historically relevant artefacts. ’Relevant’ can mean several things here, but typically would be conditioned on the task being performed by the system, and so could include RFPs that referenced the spec, past responses that won bids on that spec, redlines where legal pushed back on that spec, and so on. This approach can pay huge dividends in answer quality and latency, by surfacing the most critical insights to the deep research system quickly at query time.

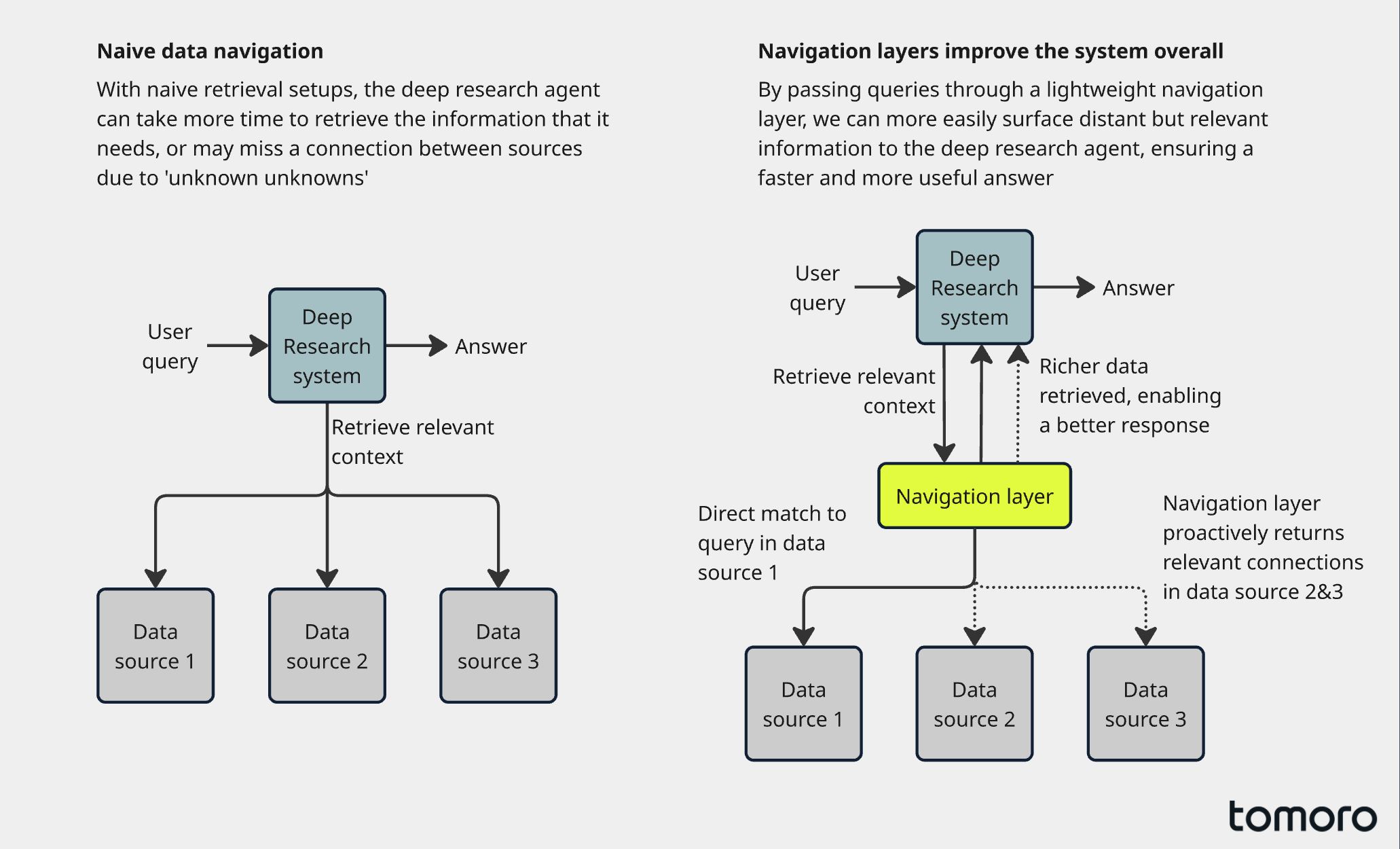

This then tees up the next question: once you have a world of sparsely connected data sources with a handful of high-signal edges, how do you stop the deep research system from wandering like a kid through a candy shop and instead get it to navigate like a seasoned analyst would?

Enterprise data sources do not behave like the web. They’re sparse, full of local conventions, and often they have exactly one “right“ source for a given fact (if you can find it). Moreover, models today have a tendency to always try to maximise recall on search questions often churning through queries to find just one more source whilst burning through latency and user patience (this can be mitigated to some degree with careful prompting).

The most effective solution to this is a lightweight tool to help the model orientate itself amongst the messy enterprise data landscape. Some teams call this an ontology. Others call it a semantic layer, a lookup service, a graph, a concept store. It doesn’t really matter.

What matters is that it gives the system a set of fast, low-cost moves so that the model can efficiently jump between the right bits of context rather than stumbling around for what feels like eternity.

A simple metaphor for this is that it’s like when you’ve just joined a new company or hopped onto a new project and your new colleagues tell you “You must bookmark these sites, you’ll use them all the time”, or “any time you have an issue with AWS just speak to Ross, he’ll get you the info you need”, and so on. Likewise, here we are simply trying to help the deep research system find what it needs quickly.

A simple metaphor for this is that it’s like when you’ve just joined a new company or hopped onto a new project and your new colleagues tell you “You must bookmark these sites, you’ll use them all the time”, or “any time you have an issue with AWS just speak to Ross, he’ll get you the info you need”, and so on. Likewise, here we are simply trying to help the deep research system find what it needs quickly.

In practice, this system doesn’t have to be complicated or manually maintained. The best implementations we have found are either generated by LLMs during the ingestion pipeline (extracting entities to populate the graph automatically) or are simple pass-throughs to existing systems of record (like a look-up against the Salesforce API). Some common examples include:

- Hash map look ups (e.g., query with product name, return product description)

- A thin “common” relationships lookup (e.g., this gene is most commonly connected to these diseases in our graph of causal gene relationships)

- Named-entity recognition models (mainly useful in areas with complex entity disambiguation problems, such as pharmaceuticals)

- For those with the most complex data relations, lightweight RDF graphs can provide the most extensible solution for an ontology

- … and more

With this in place, the system can now move through your data sources efficiently. The next question is simple: how do you know it’s doing the right thing, consistently, under real usage?

Evals, Evals, Evals

With your data now reachable and your navigation layer providing the map, your system now has the capacity to do the work. But, in an enterprise context, capacity is nothing without reliability.

This is where the biggest graveyard of AI projects lies. Many teams have fallen into the trap of “vibes-based” evaluations. They would run a query, read the output, nod approvingly, and ship it. This approach does not work when building a deep research system that might be autonomously traversing 5,000 documents to make a recommendation on a multi-million dollar supply chain decision.

The important shift here is that you’re no longer evaluating a model, you’re evaluating a system. Question interpretation, planning, tool calling, interpretation, context pruning, reranking, and even seemingly boring connector details like timestamps all show up in user experience.

Structured, repeatable evals help us solve these problems.

When building out evals we can broadly think of them as falling into three categories, ranging from the mechanical to the subjective.

1. The mechanical (the guardrails)

This is the part that feels closest to unit tests and it’s where teams can often make the fastest progress early on. These are also typically the most stable over time, once you have set these up they can keep paying dividends through the lifespan of the project.

“Mechanical evals” are generally checks that can be run on every query without a human in the loop. These help us build confidence that the system is behaving predictably and safely under real user loads.

Some examples of these include:

- Citation health: Do all citations point to spans that were actually retrieved? Are there uncited claims? Are there claims that are not supported in source material? Are citations overly generic (e.g., a whole document cited for a single claim)

- Tool hygiene: Did the system use all the tools it said it used? Did it correctly use the navigation tools? Did it format any tool requests incorrectly? Did it retry sensibly when errors were returned?

- Latency and cost budgets: Did it keep within a target time-to-first-token? Did it exceed expected tool calls or budget? Did it burn a lot of latency and compute for a marginal gain?

These sound mundane, but they are exactly the kinds of tests that keep an enterprise system from rotting.

As a real-world example, within the deep research for drug target discovery project we utilised two layers of citation checks that run on every query. First, when generating an answer, we instruct the model to produce frequent in-line citations. LLMs being able to do this reliably is also relatively recent phenomena, similarly arriving in the first half of 2025 (anybody reading this who tried to do this for meaningful amounts of data before this will understand the challenge this used to pose). With this, we can perform a set of simple regex checks to see if e.g., an article link is mentioned that was not present in the provided sources.

The second layer of checks is performed post-hoc to the streaming of the answer. First, the answer is split into chunks, and then each chunk is assessed, with the system searching for sources in the retrieved data that support the claim(s) made in that chunk. Should no supporting evidence be found, this is raised as a potential hallucination.

2. The analytic (the “how”)

If the mechanical evals are your unit tests, the analytical evals are your code review.

Here we move into a world where we are trying to understand if the system is completing work well. We tend to be interested in understanding if it is using the correct tools, pursuing the right research directions, choosing the most authoritative sources, or knowing when to stop (amongst other things).

In practice, these typically take shape as a series of question-answer (Q-A) pairs, for which e.g., sensible tool calling orders are known, or given a body of research found in the first tool, what is the correct decision to make (important to note here that the Q-A pairs don’t have to map 1:1 with the input and output of the full deep research system, we can also test subprocesses with these methods). With these labels—which can either be generated by a human labeller or a strong labelling model (strong is relative here)—we can then utilise an LLM-as-judge method to score research runs to assess their performance. By tracking these scores over time, we can understand when our changes are making directional improvements to the system, or if we have introduced any performance regressions.

Due to the higher cost of these runs, in both money and time, these should typically be run periodically either on a set time scale or ahead of version updates.

There’s also a nice second-order benefit here: these kind of analytical evaluations can directly inform upgrades to your sparse connections that we talked about earlier. If you see, repeatedly, that the model is making the same high-quality jump—e.g., “spec → historically relevant RFP examples”—even when humans don’t explicitly link those artefacts today, that’s useful. You can promote that jump into a first-class edge or shortcut, so future runs get the benefit with lower latency and higher consistency.

This is also where you catch one of the most expensive pathologies in deep research systems: the tendency to maximise recall by default. A model can always find one more source. The question is whether it should. We can adjust the model to reinforce sensible stopping behaviour where the system recognises that additional retrieval is unlikely to change the conclusion, and chooses to deliver an answer that is well-supported and addresses the user question.

3. The user (The “so what?”)

The mechanical evals tell you the system is safe. The analytical evals tell you it's competent. User evals tell you whether it's actually useful.

This is another area where many teams stumble. They build something technically impressive that nobody wants to use twice. In an enterprise context, this is the difference between a successful deployment and a costly research project.

User evaluations are fundamentally about understanding whether the system is solving the right problem in the right way. This means going beyond "did it get the answer right?" and asking "did it give me something I can act on?"

In practice, user evals typically take a few forms:

- Task completion studies: Can users actually complete their real work faster or better with the system? This isn't about whether the model could answer a question, it's about whether a real user, in their actual workflow, got what they needed.

- Qualitative feedback loops: Regular structured conversations with power users. What queries are they running repeatedly? Where do they lose trust? When do they give up and go back to the old way? These sessions often reveal failure modes that never show up in your test sets, because users ask questions in ways you didn't anticipate, or they have implicit quality bars you didn't know existed.

- Usage analytics: Which queries get re-run? Which answers get copied out and used elsewhere? Where do users click the thumbs down? Declining usage isn't always a failure (sometimes users get their answer and move on), but patterns in when and how people abandon queries tell you a lot about where the system isn't meeting expectations.

Taken together, these give you a way to measure usefulness without guessing, helping you spot problems before they start to erode user trust.

However, even a system that scores perfectly on mechanical accuracy and delights its early users can still fail the ultimate test: moving the top-line for a business. Reliability and user satisfaction are merely prerequisites for this. To cross the chasm from a successful pilot to a transformative enterprise asset, you need to look beyond how the system works and focus on where it is applied.

Converting Your Deep Research System into Top-line Business Value

We've walked through how to make your data work for your system, and then how to make your system work for your users. Now we need to talk about making this system work for your business.

There's been intense focus on this among business leaders recently, and rightly so. In the wake of reports like MIT's claim that 95% of enterprise AI projects fail to achieve ROI, the tolerance for impressive demos that don't ship has evaporated. The models are ready. The architectures are proven. The question now is: can you actually deploy this in a way that creates value for your business?

The good news is that frontier deep research systems, built on the principles above, are well positioned to clear this bar. They're not trying to automate everything or replace entire job functions. They're trying to make your best people dramatically more effective at the high-value work they already do.

But getting from “technically working” to “delivering ROI” requires a few additional unlocks: the organisational, user experience (UX), and measurement choices that determine whether this becomes an everyday tool or a forgotten tab.

In our experience, there are two.

1) Wedge selection: choose a workflow where value is legible

The temptation is often to start with low-stakes internal tasks like "summarise this meeting." While safe, these use cases rarely prove enough value to justify the cost.

Deep research systems land best when they are pointed at large, hard tasks—expensive problems where an improvement in quality or speed results in a demonstrable revenue jump or strategic advantage.

We see the highest ROI when companies target wedges such as:

- Complex Bid & RFP Generation: deep research systems can help by automatically pulling in the closest historical wins (and the losses), extracting the few clauses that always trigger redlines, finding the strongest proof points for a given requirement, and more before translating all of that into strong, coherent positioning for the tender. The metric here isn’t time saved; it’s win-rate, margin preservation, and fewer late-stage legal/commercial surprises.

- Scientific Landscape Analysis: In R&D-heavy orgs (pharma, biotech, semiconductors), the wedge is compressing weeks of literature and internal knowledge into a usable research direction. A deep research system can read across thousands of papers, patents, internal reports, lab notes, and prior program reviews to map what’s known and what’s contested to generate an evidence-backed landscape. With this, it can deliver faster iteration cycles, fewer dead-end bets, and most importantly reduce the time to first human trial.

- Market Insight: For banks and hedge funds, the value is in turning fragmented internal research (notes, models, transcripts, broker commentary) plus external signals (filings, earnings, macro prints, news) into decision-grade trade support. A deep research system can continuously build and refresh a view on a company, theme, or macro question—surface the key deltas since last week, reconcile conflicting sources, and produce an investment memo or trade packet with full provenance.

The common thread here is that these are not chats. They are complex workflows that usually require expensive external consultants or weeks of senior staff time. When you point a deep research system at these problems, the value is undeniable.

2) UX: Move from chatting to delegating, and from answers to artefacts

This is one of the user experience shifts that will define 2026.

If your deep research system is simply a chatbot that users query to find things, it can quickly regress to being used sporadically. It remains a reference tool, with users ultimately having to be the ones to compile the outputs into their desired end results. However, if it feels like an always-on analyst that you can assign work to, it can completely change the operating model of the team.

We are seeing a move away from "chatting" (short, back-and-forth turns) toward delegating (defining a scope, a template, and a goal, and letting the system run).

Three specific shifts enable this:

- Outputs as Artefacts: High-value work rarely lives in a chat window; it lives in documents, memos, and slide decks. Modern deep research systems should skip the chat phase and generate the final business artefact directly. When a user can ask for a "3-page investment memo in our corporate format" and receive a downloadable file rather than a stream of text, the time-to-value drops precipitously. This is also commonly extended into scheduled generations, wherein users can ask for emails or reports to automatically be generated with new insights and distributed to relevant parties as new data emerges.

- Local Optimisation via Custom Templates: Models have become robust enough that we can now let business units or even individual users shape their own prompts and behaviours without breaking the system. A risk report looks different in London than it does in New York. By allowing teams to upload or design their own structural templates and defining their own stopping criteria (e.g., "always check these three specific internal databases") or output format, your users can get a lot more value from the system, and create something they want to use more and more.

- Trust as an Interface: When a user delegates a task that takes 20+ minutes to run, trust becomes a high priority problem. You cannot present a black box. The interface must expose the system's thinking and choices, showing the user which tools are being used, generating citations, and more. We often find that the best UX experience for these systems surface high level insights on the progress of the research by default, and provide the option for the user to dig deep by expanding for more information in a sidebar or the like.

The Path Forward

We envision a future where every leading enterprise has a tailored deep research system sitting behind its most critical workflows. This will take shape as a series of always-on analysts that can reliably traverse thousands of internal artefacts and produce decisions and deliverables people can act on. As frontier models raise the execution ceiling, the differentiator shifts to the fundamentals: making your data reachable, giving the system a map, and operationalising reliability through evals.

The model capability gains we’ve seen over the last year are the clearest signal of where this is heading. The opportunity for leaders in 2026 is to move early. Pick a wedge where value is legible, earn trust through provenance and guardrails, and convert your enterprise deep research solution from a pilot into a compounding capability the business uses every day.