The Next Frontier of AI Reasoning: Marrying LLMs with Formal Solvers

Large Language Models (LLMs) have made extraordinary progress in understanding natural language, generating fluent responses, and powering entirely new customer and employee experiences. However, LLMs are stochastic in nature and hence using it to perform complex numerical or logical reasoning have weak guarantees that their outputs will be compliant or optimal. Some examples:

- A manager tells an AI planner assistant “Ship as much as possible next week while keeping costs low,” and the system delivers an aggressive plan that looks efficient, but silently exceeds warehouse capacity and breaks delivery guarantees.

- A coordinator requests to an AI assistant “Reassign crews to reduce overnight stays and minimise disruption,” and the model produces a lower-cost schedule that looks optimal but violates mandatory duty-time or rest constraints

- A financial operations AI assistant is asked to approve transactions under strict regional and risk constraints, but clears a suspicious transaction by inventing a rationale that sounds compliant while violating internal policy.

Therefore, in environments that require strict operational constraints, combining LLMs with complementary formal solvers is necessary to ensure that natural-language-driven decisions always remain within defined operational boundaries to avoid infeasible, sub-optimal or non-compliant outputs.

This is where our R&D team at Tomoro has been investigating a hybrid paradigm that fuses the creativity and flexibility of LLMs with the rigour, guarantees, and transparency of formal mathematical solvers (e.g Z3, pyomo, or-tools etc) and building a reusable Formal-AI engine to make this capability a standard part of the enterprise stack. This platform will allow organisations to ingest business rules directly from their existing systems, continuously verify decisions against those rules, and safely deploy AI agents that operate within clearly defined boundaries.

Our vision is for enterprises to reduce operational risk while accelerating decision‑making at scale. Leaders gain faster, policy‑compliant decisions directly from natural‑language inputs, while organisations can automate adhoc changes in scheduling, resource allocation across supply chains, finance, policies verification or even generation of videos or 3D designs, with guarantees that infeasible, non‑compliant, or unsafe outcomes are blocked before they reach production.

In controlled experiments across logistics-style optimisation problems and three public benchmarks, our hybrid approach consistently demonstrated:

- Higher accuracy

- Higher Interpretability and Auditability

The Hybrid Architecture

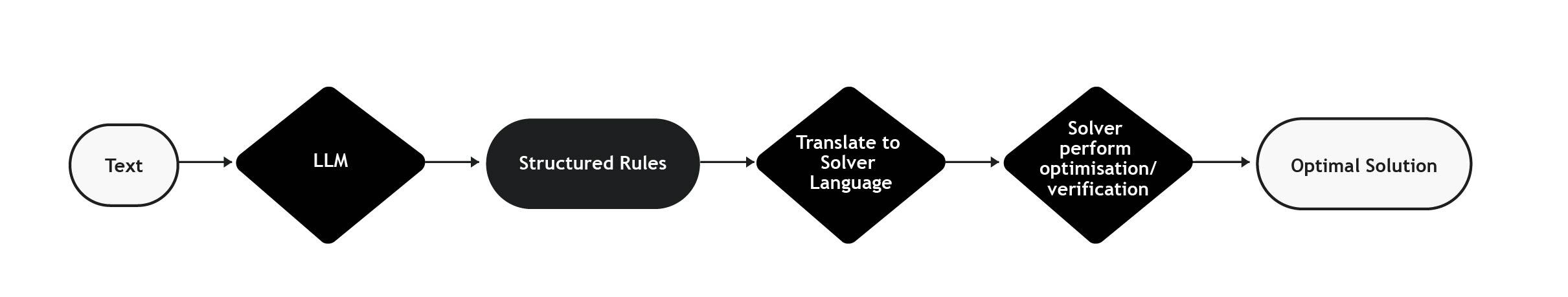

Our approach flips the usual “LLM does everything” paradigm and instead follows this design:

This cleanly separates the responsibilities of both, leveraging the strengths of LLMs to perform extraction of rules and constraints from natural language, and uses deterministic solvers (e.g or-tools, z3, pyomo) to perform deterministic optimisation or verification. This gives us the best of both worlds:

| LLMs | Solvers | Hybrid (LLM + Solver) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understand human intent across different domains | ✅ Excellent | ❌ None | ✅ Excellent |

| Deterministic behaviour | ❌ No | ✅ Guaranteed | ✅ Yes |

| Provably correct in mathematical reasoning and optimisation across multiple constraints | ⚠️ Fragile | ✅ Guaranteed | ✅ Yes |

| Auditability & interpretability | ⚠️ Fragile | ✅ Clear | ✅ Clear |

| Resistant to prompt noise / injection | ❌ Vulnerable | ✅ Immune | ✅ Strong |

Experimental Track 1: Logistics / Workers Assignments

The problem domain

We started with a challenge that some of our clients face:

- Turning natural-language requests into real-time, optimal resource decisions, while strictly enforcing operational, policy, and cost constraints.

This problem sits at the heart of modern logistics and supply chains: workforce scheduling, asset allocation, routing, fulfilment planning, and capacity management. It’s also where LLMs and formal solvers needs to be combined to produce trustworthy systems. To run the evaluation, we constructed controlled test scenarios, data sources and constraints along with 240 synthetic queries to simulate this scenario. Here are some similar examples of queries we are tackling:

- Please revise the existing schedule following a cancellation. The target facility must be fully supplied by 24 December 2025. Prefer to source inventory from a nearby warehouse if available, and to route through a specific consolidation point if possible. Earliest allowable start date is 14 December 2025.

- Last minute request, VIP is arriving in location A in 3 hours. We need the required number of relevant staff types on site in 2 hours. Adjust the staff allocation please, prefer to minimise changes from existing allocations

We can see from the queries that the system must reliably extract and enforce hard and soft constraints directly from natural-language requests:

- Hard constraints are non-negotiable (e.g earliest date, contractual terms, capacity ceilings). Violating any one of them invalidates the solution.

- Soft constraints encode preferences (e.g minimising delays, reducing cost, minimise changes) where the objective is to optimise without ever crossing hard boundaries.

Furthermore, some aspects of these optimisation problems can’t be fully predefined. They must be assembled dynamically, not only pulling pre-defined constraints and objectives from structured business logic, internal documents, operational data, but also from the user’s text request itself.

The Approaches We Evaluated

To understand how different techniques perform in this setting, we implemented and compared three approaches.

- Pure LLM: The simplest approach: all relevant data and the user’s natural-language request are passed into a single LLM prompt, which is asked to produce an optimal plan or allocation.While this can work for small or loosely constrained problems, it breaks down as complexity increases. The model may ignore constraints, prioritise the wrong objective, or produce plans that sound reasonable but are infeasible in practice, without any reliable way to detect or prevent failures.

- LLM + Code Interpreter: In this setup, the LLM still interprets the request, but is equipped with tools to access data sources and generate executable code to perform optimisation.This adds flexibility and observability, but reliability remains an issue. The LLM is still responsible for translating constraints into correct code logic, and small reasoning or coding errors can lead to invalid or suboptimal outcomes, especially as constraints scale.

- Hybrid: LLM → Structured Constraints → Deterministic Solver: The third approach cleanly separates responsibilities. The LLM never “decides” the outcome. It helps formalise the variables, constraints and objectives. A proven optimisation solver then enforces constraints, guarantees feasibility, and produces results that can be verified and audited.The LLM’s role is limited to translating natural-language requests into explicit, structured constraints using predefined schemas. These constraints are then automatically compiled into solver code (e.g. or-tools), which deterministically computes a feasible and optimal solution.

Results

We tested the methods using several LLMs model (GPT 5, 5.1, 5.2 etc) and unsurprisingly, the hybrid method (method 3) outperformed the others:

| Method | Assignment Accuracy | Avg Latency | Tokens Used / query |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure LLM | 70 – 78% | 62 – 190s | ~175k |

| LLM + Code Interpreter | 82 – 84% | 62 – 140s | ~9k |

| LLM → Solver (Hybrid) | 95 – 97% | 6 – 25s | ~2k |

Our hybrid method not only shows a jump in accuracy, but also with over 4× token efficiency and order-of-magnitude lower latency.

Experimental Track 2: General-Purpose Optimisation from Natural Language

Our next step is to explore building a generalisable and reusable interface that converts natural language into structured semantic representations, which our backend can translate into solver-ready code. For this experiment, we mainly focus on Linear Optimisation problems. We evaluated it on 3 public datasets (NLP4LP, NL4OPT, IndustryOR)

The Approaches We Evaluated

- Vanilla LLM

- Where we directly input the whole text problem into the LLM

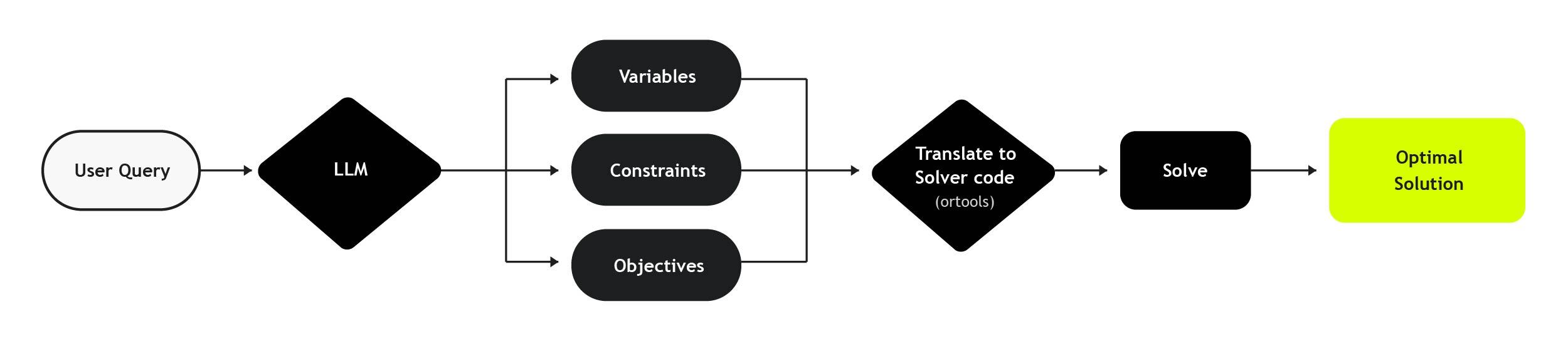

- Hybrid Method (LLM → Structured Rules → Solver → Verified Output)

- We use LLM to extract variables, constraints, objective from the text input to formulate a structured optimisation problem

- Pass the structured optimisation problem along with the original problem to an LLM for self-verification

- Auto-translate the structured optimisation problem to or-tools to solve and compute the optimal assignment

Refer to the Appendix B for an example on how our hybrid method parses and formulates the problem from text.

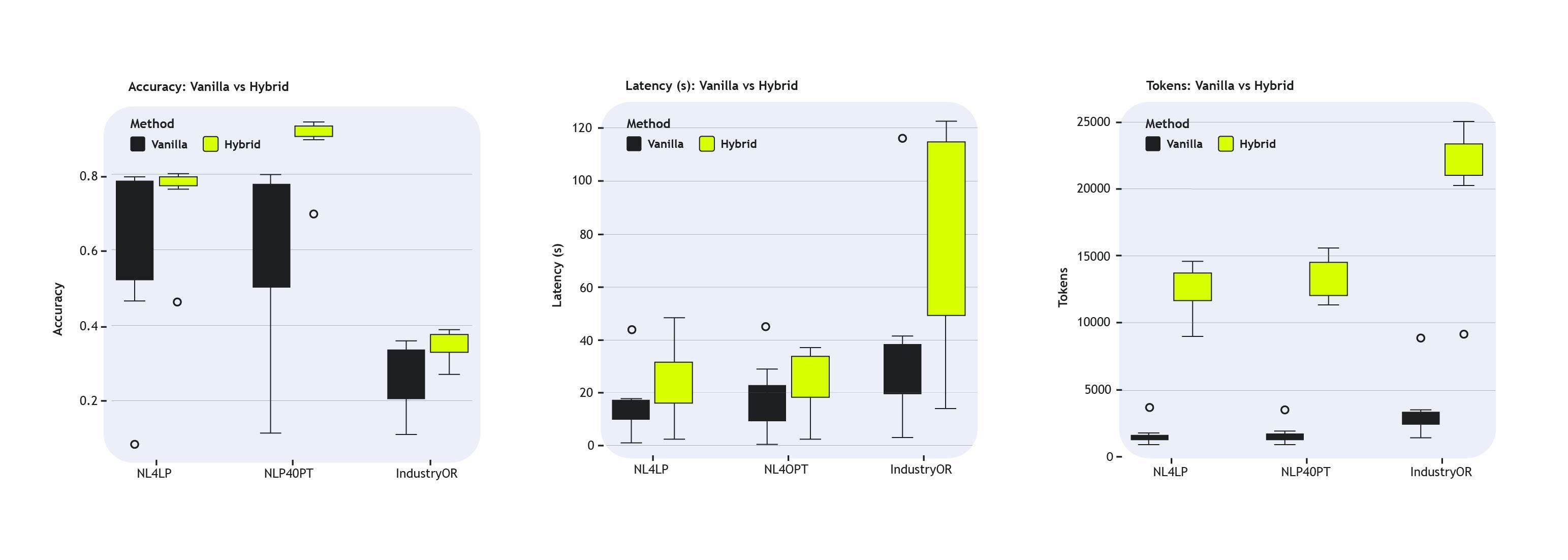

Results

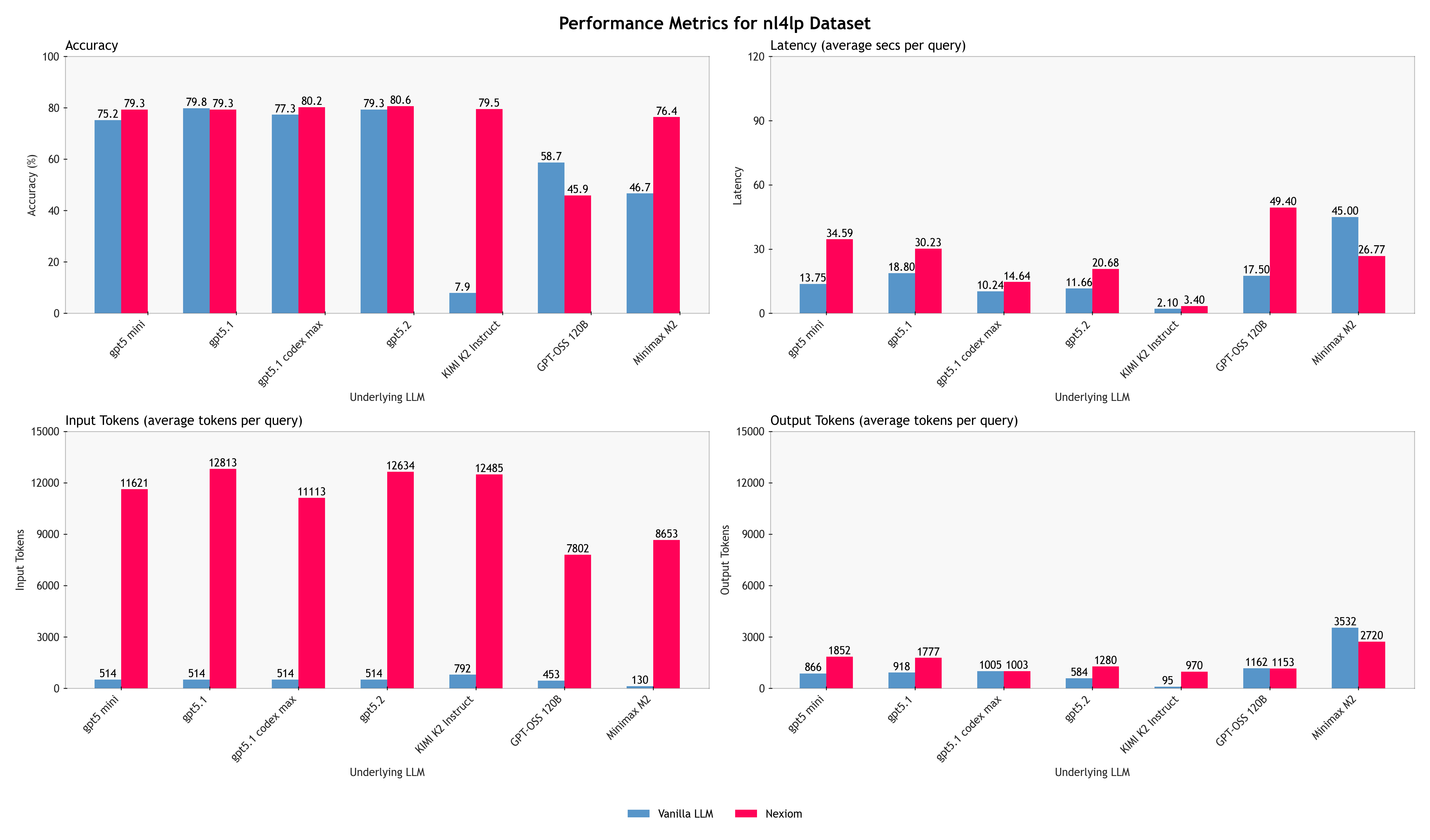

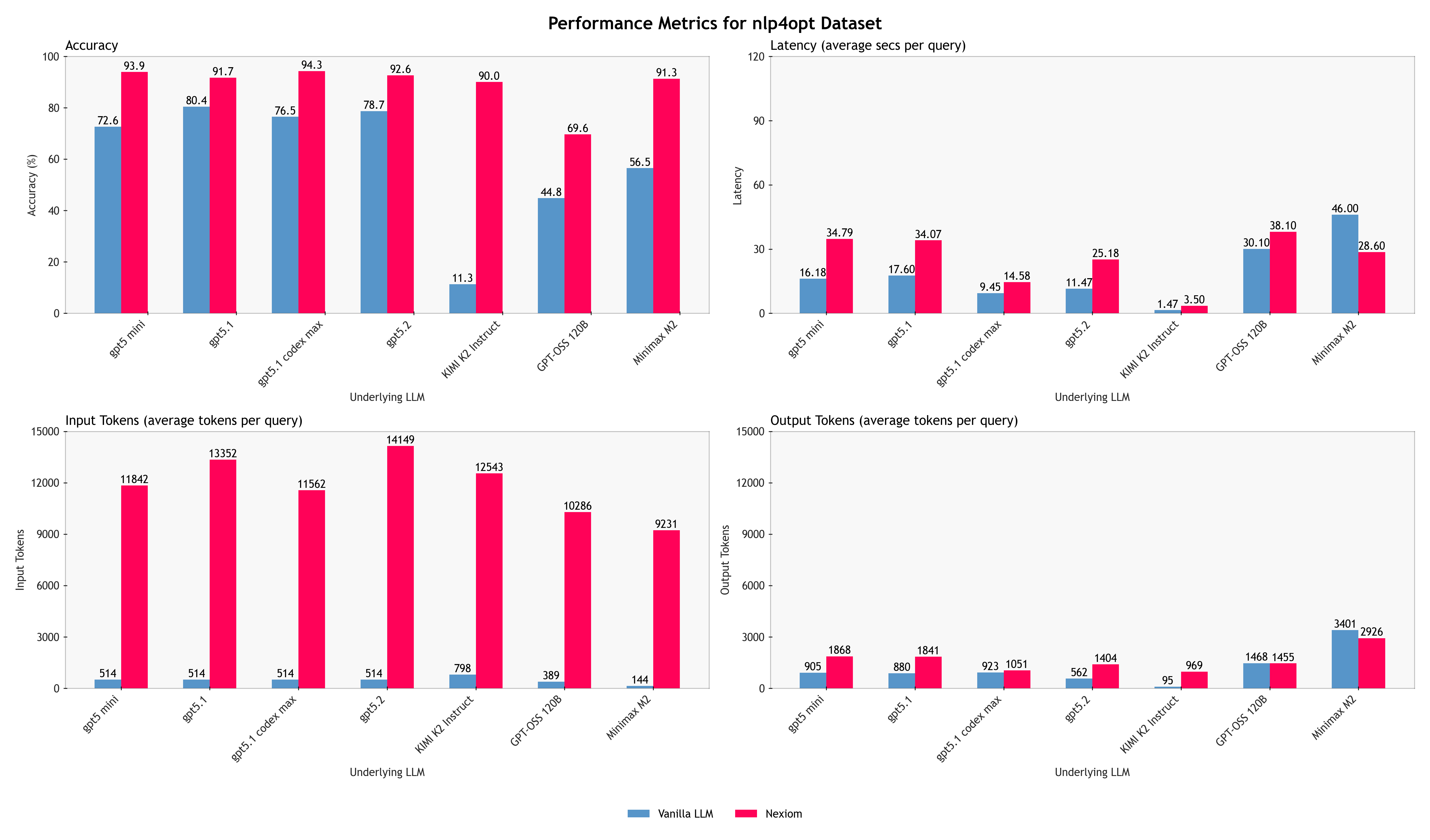

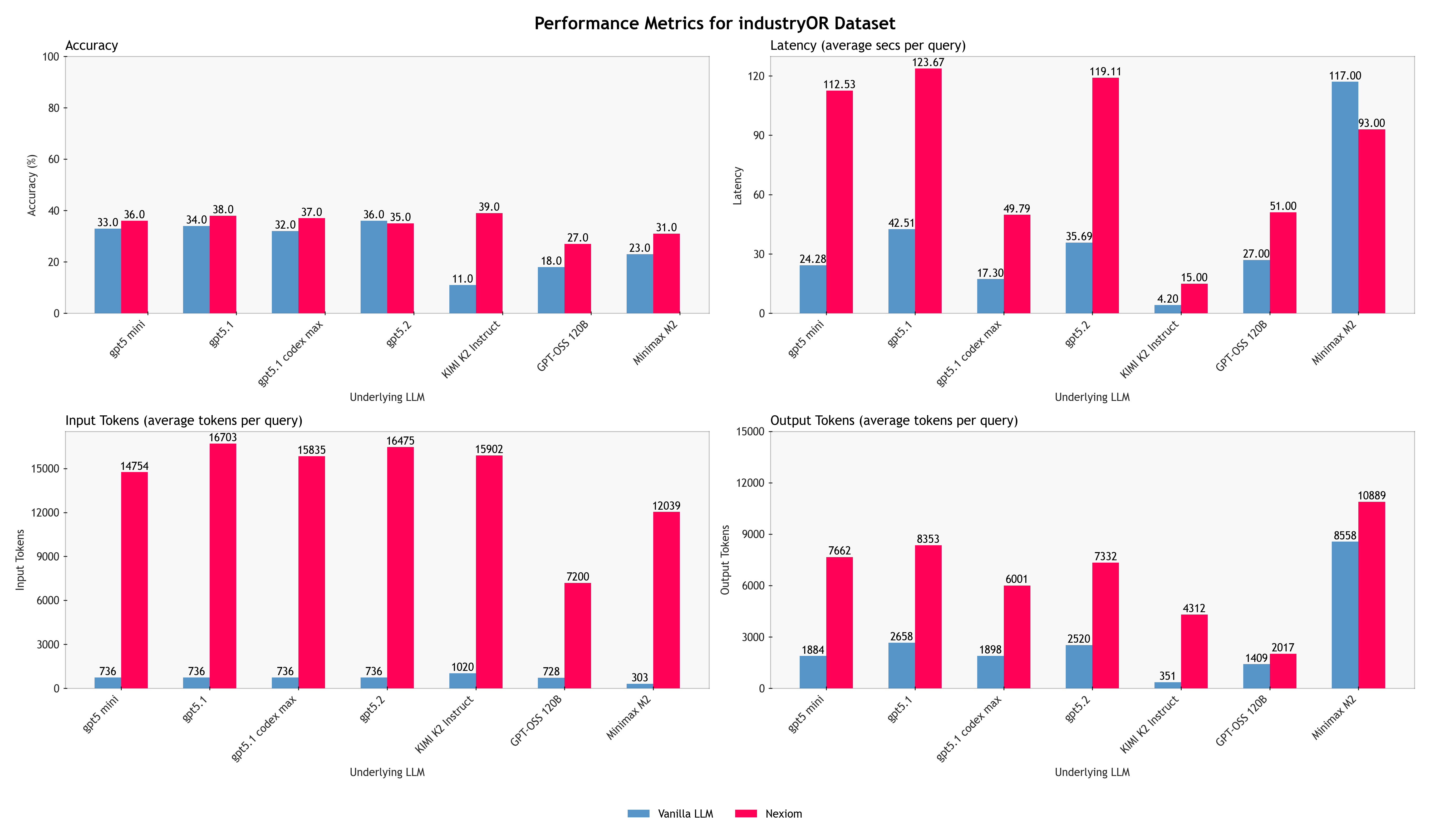

We evaluated this methodology across both proprietary frontier models (GPT 5.1, GPT 5-mini, GPT5.1-codex-max, GPT 5.2) and open-source models (Kimi K2, GPT-OSS models, and Minimax M2). The boxplots here summarises the results for each method. For more detailed results on the different underlying models for each method, please refer to the bar charts in the Appendix C.

The hybrid approach consistently delivers more accurate, stable, and verifiable results than a pure LLM baseline, across almost all of the underlying language models evaluated. While absolute performance varies across models, as expected, the relative gains from the hybrid approach remain consistent. This shows that the improvements are not driven by any single model’s reasoning ability, but by the architectural separation between natural-language understanding and formal optimisation.

Accuracy

On NLP4LP and NL4OPT, which primarily consist of linear programming problems the hybrid method achieves near-ceiling accuracy, outperforming pure LLM prompting. Instead of “approximately correct” reasoning, the hybrid system produces better-formed valid mathematical formulations more consistently. On the more challenging IndustryOR dataset, overall accuracy drops for both methods, but for different reasons. Many IndustryOR problems involve combinatorial structures such as vehicle routing, task sequencing, or workforce assignment variants that go beyond the linear optimisation capabilities currently supported by our solver backend.

When analysing the failure modes, its noticeable that vanilla LLM frequently violates required constraints, as shown in these examples:

Example 1:

"A body builder buys pre prepared meals, a turkey dinner and a tuna salad sandwich. The turkey dinner contains 20 grams of protein, 30 grams of carbs, and 12 grams of fat. The tuna salad sandwich contains 18 grams of protein, 25 grams of carbs, and 8 grams of fat. The bodybuilder wants to get at least 150 grams of protein and 200 grams of carbs. In addition because the turkey dinner is expensive, at most 40% of the meals should be turkey dinner. How many of each meal should he eat if he wants to minimise his fat intake?"In the pure vanilla method, the LLM outputs a numerically lower-fat solution but it violates the “at most 40% of the meals should be turkey” constraint whereas the hybrid method correctly enforces this hard constraint to get the valid answer.

Example 2:

"A patient in the hospital can take two pills, Pill 1 and Pill 2. Per pill, pill 1 provides 0.2 units of pain medication and 0.3 units of anxiety medication. Per pill, pill 2 provides 0.6 units of pain medication and 0.2 units of anxiety medication. In addition, pill 1 causes 0.3 units of discharge while pill 2 causes 0.1 units of discharge. At most 6 units of pain medication can be provided and at least 3 units of anxiety medication must be provided. How many pills of each should the patient be given to minimise the total amount of discharge?"In the pure vanilla method, the LLM again outputs a numerically lower discharge solution but it exceeds the maximum allowed pain medication constraint, whereas the hybrid method correctly enforces this hard constraint to get the valid answer.

Latency and Token Usage

The latency and token usage data reveal an important and often misunderstood distinction. The results show that the hybrid approach incurs higher average latency and tokens than a single-shot pure LLM prompt but this is expected and largely attributable to architectural choices rather than inefficiency.

The hybrid pipeline includes:

- One or more LLM calls to extract structured variables, constraints, and objectives

- A self-verification step to catch internal inconsistencies

While this adds overhead compared to a single prompt, latency remains bounded and predictable, and solver execution itself is typically fast once the problem is well-formed. The extra overhead is spent on creating explicit, reusable, and auditable intermediate representations. Pure LLM approaches, by contrast, compress reasoning into a single opaque generation, shifting cost into retries, manual checks, or downstream failures. Moreover, much of this overhead can be optimised in future iterations through:

- Caching extracted schemas,

- Incremental constraint updates,

- Tighter prompt and call orchestration.

Transparency and Auditability

Finally, even in cases where both methods fail, the failure mode itself is fundamentally different.

- When using Vanilla LLM method, failures are often silent: the solver returns a result, but it might be subtly wrong.

- In the hybrid approach, there is full transparency and interpretability as the problem formulation and breakdown is explicit, which means it is much easier for anyone to understand which parts of the formulation causes the error.

Future extension of this system could even expose these in an interface to users for auditing or verification before actual execution of the solver. This transparency not only improves measured accuracy, but also makes the system easier to debug and improve, which is critical for real-world deployment.

Key Takeaway

Across all benchmarks and most of the underlying models tested, the results reinforce a central conclusion of our work:

LLMs are powerful at understanding and translating intent, but deterministic solvers are essential for enforcing correctness.

The hybrid approach transforms natural language from a source of ambiguity into a reliable interface for mathematically sound decision-making, bringing enterprise AI one step closer to systems that are not just intelligent, but trustworthy.

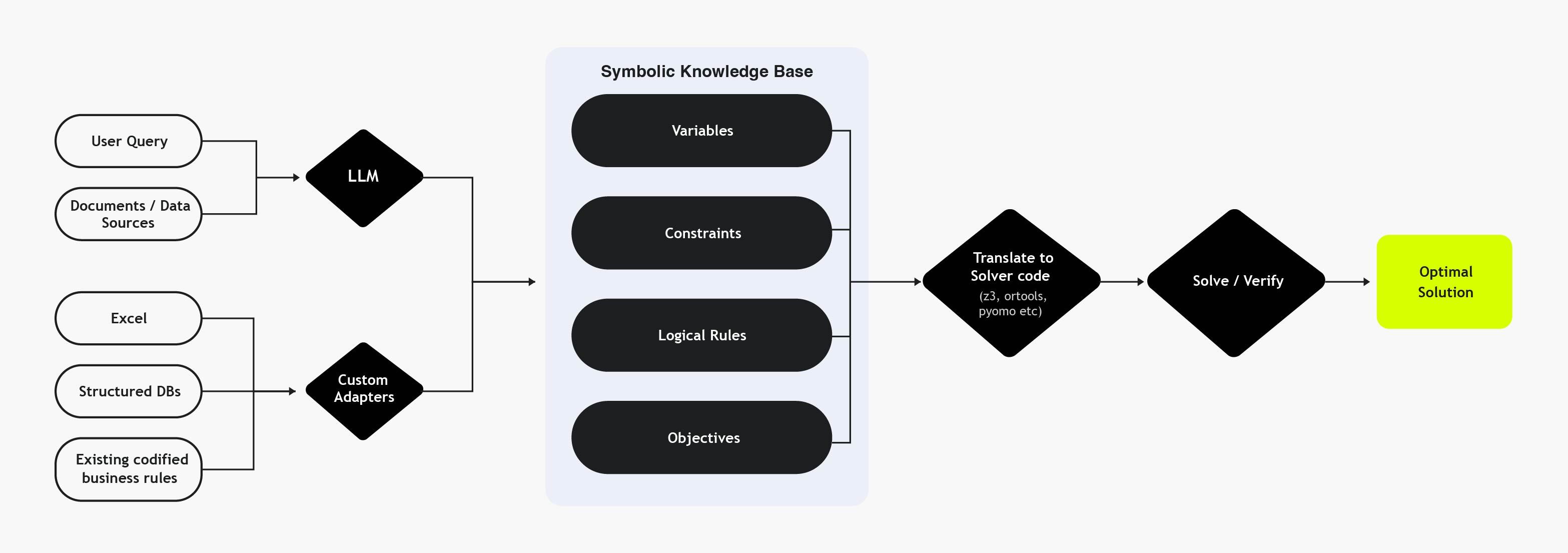

What’s Next: A Reusable Formal-AI Engine for the Enterprise

In reality, enterprise constraints don’t live in neat schemas or perfectly phrased prompts. They’re scattered across databases, spreadsheets, internal policies and contracts. User requests are often incomplete, ambiguous, or ask for things the business simply doesn’t allow. To make this paradigm work at scale, we’re building a reusable backend engine that turns this complexity into something enterprises can actually rely on.

The Platform

At its core, this engine acts as a formal backbone for AI-driven decision systems, providing:

- Symbolic knowledge base with adapters to ingest business rules, constraints, variables, objectives

- Translation layer that compiles schemas into solvers’ code

- Interfaces for teams to inspect, audit, and modify constraints

Where This Unlocks Value

Although the above experiments focuses on optimisation problems currently, this method can be extended to handle logical verification problems. Some potential business applications:

- Ad-hoc dynamic scheduling, routing, resource allocations can be done quickly with guaranteed constraints

- Get answers and recommendations that always respect business rules.

- Design and validate complex 3D objects, videos, and architectures with hard constraints, catching infeasible designs before they hit production.

Closing Thoughts

AI today is powerful, but enterprises don’t just need power, they need correctness, consistency, and control.

Tomoro’s hybrid LLM-Solver system is our step toward a world where:

- Agents don’t hallucinate rules and constraints

- Logical deduction and optimisation is mathematically sound

- Natural language becomes the universal interface to deterministic systems.

Appendix

Appendix A: Sample Questions / Answer from the Public Natural Language Optimisation Datasets

NLP4LP Dataset Example

{"question": "A laundromat can buy two types of washing machines, a top-loading model and a front-loading model. The top-loading model can wash 50 items per day while the front-loading model can wash 75 items per day. The top-loading model consumes 85 kWh per day while the front-loading model consumes 100 kWh per day. The laundromat must be able to wash at least 5000 items per day and has available 7000 kWh per day. Since the top-loading machine are harder to use, at most 40% of the machines can be top-loading. Further, at least 10 machines should be front-loading. How many of each machine should the laundromat buy to minimise the total number of washing machines?", "answer": 67, "ori": "14_nlp4lp", "index": 1}

NL4OPT Dataset Example

{"question": "There has been an oil spill in the ocean and ducks need to be taken to shore to be cleaned either by boat or by canoe. A boat can take 10 ducks per trip while a canoe can take 8 ducks per trip. Since the boats are motor powered, they take 20 minutes per trip while the canoes take 40 minutes per trip. In order to avoid further environmental damage, there can be at most 12 boat trips and at least 60% of the trips should be by canoe. If at least 300 ducks need to be taken to shore, how many of each transportation method should be used to minimise the total amount of time needed to transport the ducks?", "answer": 1160, "ori": "5_nl4opt_test", "index": 1}

IndustryOR Dataset Example

{"question": "A company has three tasks that require the recruitment of skilled workers and labourers. The first task can be completed by a skilled worker alone or by a team consisting of one skilled worker and two labourers. The second task can be completed by either a skilled worker or a labourer alone. The third task can be completed by a team of five labourers or by a skilled worker leading three labourers. It is known that the weekly wages for skilled workers and labourers are 100 yuan and 80 yuan, respectively. They work 48 hours per week, but their actual effective working time is 42 hours and 36 hours, respectively. To complete these three tasks, the company needs a total effective working time of 10,000 hours for the first task, 20,000 hours for the second task, and 30,000 hours for the third task. The number of workers that can be recruited is limited to a maximum of 400 skilled workers and 800 labourers. Establish a mathematical model to determine the number of skilled workers and labourers to recruit in order to minimise the total wage expenditure.", "answer": 44480, "ori": "6_industryor", "index": 51}Appendix B: How our Hybrid Method Parses and Formulates the Problems

# Query

"A laundromat can buy two types of washing machines, a top-loading model and a front-loading model. The top-loading model can wash 50 items per day while the front-loading model can wash 75 items per day. The top-loading model consumes 85 kWh per day while the front-loading model consumes 100 kWh per day. The laundromat must be able to wash at least 5000 items per day and has available 7000 kWh per day. Since the top-loading machine are harder to use, at most 40% of the machines can be top-loading. Further, at least 10 machines should be front-loading. How many of each machine should the laundromat buy to minimise the total number of washing machines?"

# LLM automatically extract variables, constraints, objectives in this structured format

{

"variables": [

{

"name": "top_loaders",

"type": "integer",

},

{

"name": "front_loaders",

"type": "integer",

}

],

"constraints": [

{

"operator": ">=",

"left": { "var": "top_loaders" },

"right": 0

},

{

"operator": ">=",

"left": { "var": "front_loaders" },

"right": 10

},

{

"operator": ">=",

"left": {

"op": "add",

"terms": [

{ "op": "mul", "coef": 50, "var": "top_loaders" },

{ "op": "mul", "coef": 75, "var": "front_loaders" }

]

},

"right": 5000

},

{

"operator": "<=",

"left": {

"op": "add",

"terms": [

{ "op": "mul", "coef": 85, "var": "top_loaders" },

{ "op": "mul", "coef": 100, "var": "front_loaders" }

]

},

"right": 7000

},

{

"operator": "<=",

"left": {

"op": "sub",

"left": { "op": "mul", "coef": 0.6, "var": "top_loaders" },

"right": { "op": "mul", "coef": 0.4, "var": "front_loaders" }

},

"right": 0

}

],

"objective": {

"sense": "minimise",

"expression": {

"op": "add",

"terms": [

{ "var": "top_loaders" },

{ "var": "front_loaders" }

]

}

}

# Deterministic Backend will automatically convert these structured schemas into or-tools code

##...boilerplate code...

top_loaders = solver.IntVar(0, solver.infinity(), "top_loaders")

front_loaders = solver.IntVar(10, solver.infinity(), "front_loaders")

solver.Add(50 * top_loaders + 75 * front_loaders >= 5000)

solver.Add(85 * top_loaders + 100 * front_loaders <= 7000)

solver.Add(0.6 * top_loaders - 0.4 * front_loaders <= 0)

solver.Minimise(top_loaders + front_loaders)

status = solver.Solve()

## ...boilerplate code...Appendix C: Detailed Results for Experiment 2